Body arts pioneer Fakir Musafar dies

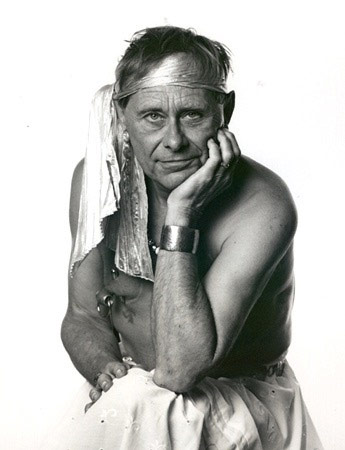

Fakir Musafar, an icon of the modern body modification culture, died at his home in Menlo Park August 1. He announced in May that he was fighting advanced lung cancer. He was 87.

Born Roland Loomis, Fakir, as he was known, was widely known as a body modification pioneer and founder of the “modern primitive” movement. He was a photographer, performance artist, and taught body piercing and body play rituals to countless students worldwide.

“He never set out to make a show of crashing through social and sexual barriers,” said longtime friend Patrick Mulcahey. “His earliest experiments in bondage, sensation, and out-of-body journeys were performed entirely in secret. He wasn’t so much about breaking boundaries as he was just blind to them.”

Fakir was born August 10, 1930, in Depression-era Aberdeen, South Dakota. He went to school with children from the local Sioux Indian reservation, learning from them about Native American culture.

Fakir recalled being a bright and solitary boy who read encyclopedias from cover to cover, taking a particular interest in tribal cultures and their rituals. As recounted in his 2002 photography book “Spirit + Flesh,” as a teenager he began experimenting with body piercing and self-bondage in his family’s cellar.

Fakir earned a degree in electrical engineering from Northern State University and, many years later, a master’s in creative writing from San Francisco State University.

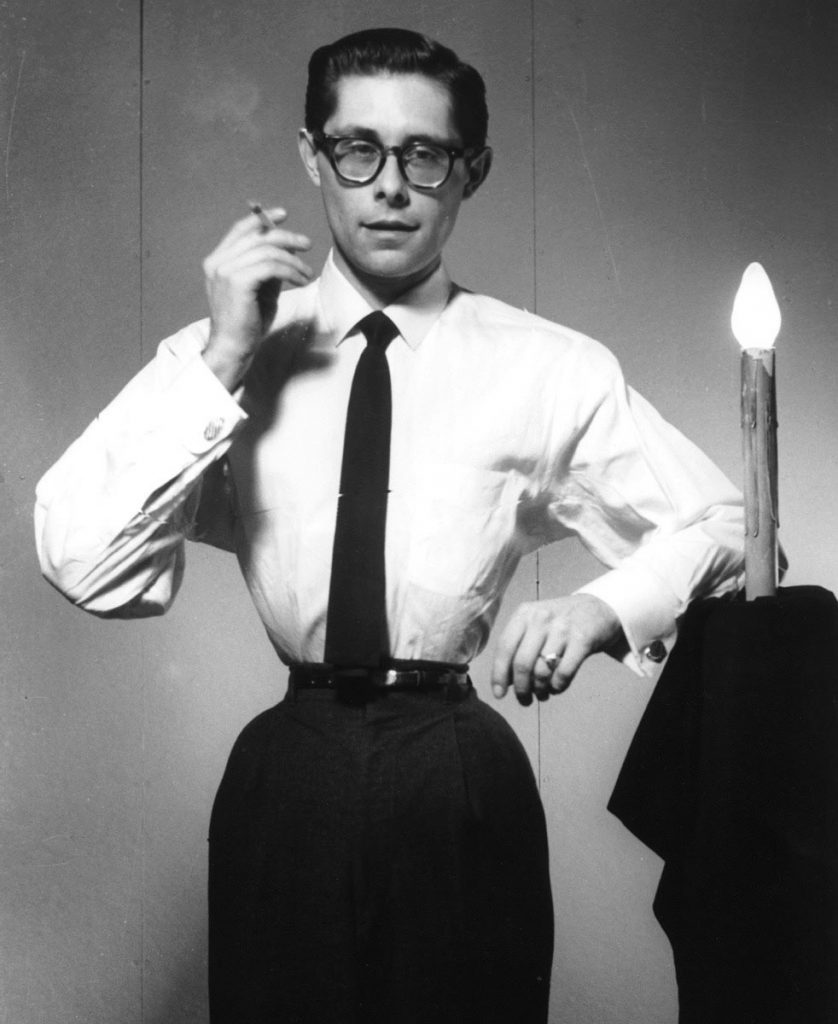

By the time he was working as an advertising executive in San Francisco and Silicon Valley in the 1950s and 1960s, his solo explorations had evolved to include hook suspensions, extreme corseting and other body rituals, much of which he documented in self portraits.

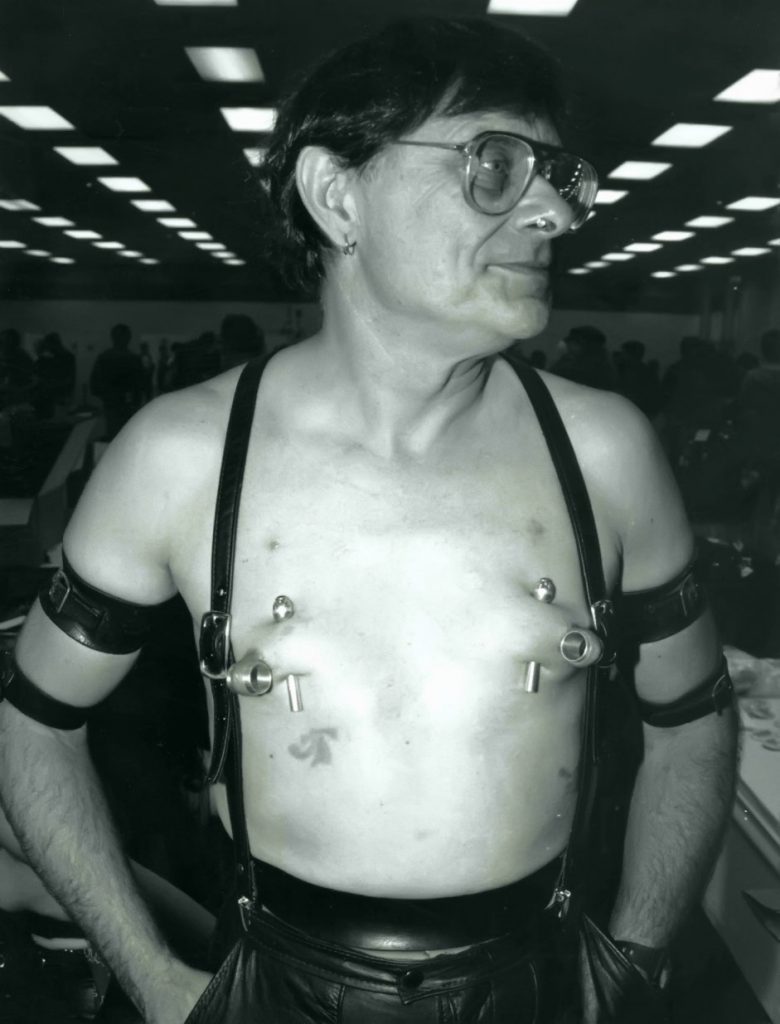

In the 1970s and 1980s, Fakir began to connect with others who shared his interests. He recalled that he initially went public at an international tattoo convention in Reno in 1977. Fakir became involved with the gay leather community in Los Angeles, the Society of Janus, and the sex radical scene in New York City. Over his lifetime he embraced multiple sexual and gender identities.

“Fakir and I became friends in 1982 when he was a nerdy advertising exec with ink-stained pockets and largely in the closet,” artist and former porn star Annie Sprinkle told the Bay Area Reporter. “Gradually he started fully living his dream. His life is a testament to following your bliss, without shame, and to enjoying one’s body.”

Fakir gained wider attention with the 1985 film “Dances Sacred and Profane,” in which he and Gauntlet founder Jim Ward participated in a sun dance, a Native American ritual that involves pulling against hooks in the flesh. His fame grew with the 1989 publication of the RE/Search book “Modern Primitives,” a term he claimed to have coined.

Identifying as a shaman, Fakir emphasized the spiritual aspects of physical rituals, which offer a way to connect with ancient wisdom. He participated in Black Leather Wings, a radical faerie group incorporating BDSM and pagan rituals, and recreated the Hindu Kavandi and ball dance rituals.

Fakir was frequently asked about appropriation of rituals from other cultures.

“You can see it through the eyes of your own culture but you can still catch the fire … Fire is fire, no matter where it burns,” he said in a 1992 interview. “I may have been inspired by them, but much of what I’ve done has been quite different. But I thank them and I’m very appreciative that I’ve had a chance to be inspired to do anything at all.”

Over the years Fakir appeared in numerous documentaries, his writing and photography were featured in many magazines and anthologies, he lectured at universities and exhibited his work in galleries around the world, and he published his own magazine, Body Play & Modern Primitives.

“Fakir’s every movement was a beautiful dance of exuberance,” artist and filmmaker Madison Young, who displayed his work at her former San Francisco gallery Femina Potens, told the B.A.R. “When I think of Fakir, I think of his passion, his joy, his transcending light, his magic, his epic fearless commitment to life, art, community, and the body as art. His radiant spirit always transcended well beyond the flesh and it always will.”

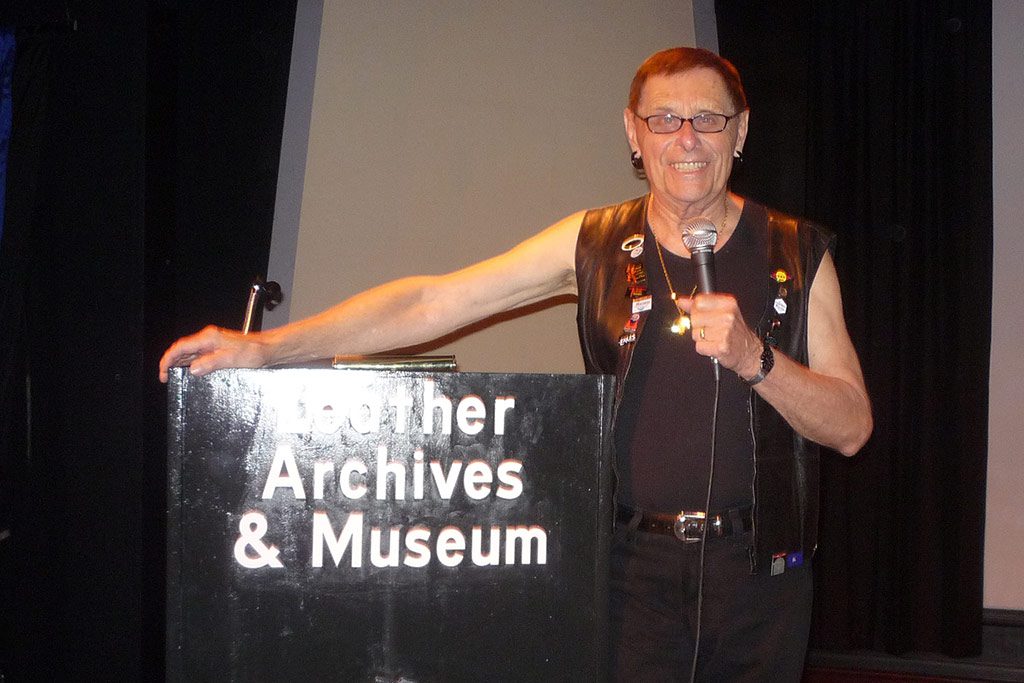

In his later years, Fakir largely focused on education, teaching body modification skills and ritual at his Fakir Body Piercing and Branding intensives workshops.

“I am grateful and honored beyond words to have known you – all of you who have been touched by my presence and followed my example,” he wrote in a Facebook announcement about his cancer in May. “I never expected our passions and practices to grow to a global phenomenon … Thank you for embracing, growing, and embodying our art, craft, and energetic ritual practices. They have changed the cultural landscape worldwide.”

Fakir’s archives and memorabilia are held by the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, the Leather Archives & Museum in Chicago, and the Association of Professional Piercers.

Fakir is remembered by his wife, Carla Loomis (aka Cleo Dubois), and his chosen family, loved ones, and students in the Bay Area and throughout the world. A celebration of his life is scheduled for November 4, at 2 p.m. at Public Works, 161 Erie Street in San Francisco.

“Fakir was one of those rare treasures among us that quietly went about the work of making the world a little bit better with everything he did,” said B.A.R. leather columnist Race Bannon. “Demonstrating to the world the power of being a kinky man living out loud and proud long before it was more commonplace. Helping others revel in their own forms of transformative spirituality. Passing down his knowledge and skill to future generations through teaching. Fakir will be missed, but not forgotten. His influence is vast and has touched millions of people, whether they might realize it or not.”

This article was originally published in the Bay Area Reporter and written by Liz Highleyman.

Fakir Musafar, guru to piercers, tattooers and other ‘body play’ artists

Fakir Musafar, a gasp-inducing practitioner and leading advocate of “body play” — the term he used to describe piercing, branding, tattooing, footbinding, corseting, body suspension and other practices that stretch, contort or otherwise alter the human form — died Aug. 1 at his home in Menlo Park, Calif. He was 87.

The cause was lung cancer, said his wife, Cléo Dubois.

A self-described “shaman, artist, master piercer and body modifier,” Mr. Musafar was “an astronaut of inner spaces,” the photographer Charles Gatewood once said, part of a “sub-sub-subculture” that crept into public view in the 1970s.

Initially centered on the gay sadomasochism and fetish communities of San Francisco and Los Angeles, it spawned what Mr. Musafar described as an international if occasionally over-the-top movement, in which entertainment sometimes replaced what he saw as the spiritual nourishment attainable through body play.

“By using your body, modifying your body, you can go into states of consciousness and discover the true nature of life and yourself,” he told Shannon Larratt, founder of the body modification website BMEzine.

Mr. Musafar called himself a “modern primitive” — a phrase that became the title of an influential 1989 book, dubbed the “body-mod bible” by the New York Times — and traced his practices to ancient traditions, drawing inspiration from sources including Islamic mysticism, Hinduism, Native American ceremonies, and the tattooing cultures of Borneo and the Marquesas Islands.

He began with clothespins, using them to stretch his skin in childhood, and at 14 made his first piercing, inspired by a photo in National Geographic of a South Seas islander who had bored a hole in his nostril.

Inserting a nail into one side of a clothespin, creating a clamp, he pierced his genitals, the one place he believed his body modifications would go unseen. “I put in a little copper ring,” he told Larratt in 1997, by then in his late 60s, “and I still have that piercing today.”

Mr. Musafar gave himself his first tattoo as a teenager, using his mother’s sewing needles, India ink and Listerine as an antiseptic. About that same time, inspired by a photo of “a wasp-waisted boy” from tribal New Guinea, he began cinching a belt around his waist at night, drawing it tighter until he experienced “shifts in consciousness.” He later used corsets of his own design to narrow his midriff by about half, giving himself a 19-inch waist.

While Mr. Musafar’s practices grew increasingly exotic as he got older — at one point he hung two dozen one-pound weights from piercings on his chest — he kept them secret from all but his closest friends, using his birth name of Roland Edmund Loomis while working as an ad man in Silicon Valley.

He “came out,” as he put it, at an international tattoo convention in 1977, when he performed in Reno, Nev., using the Musafar name for the first time. He said he adopted it after reading a Ripley’s Believe It or Not cartoon about Musafar, a Persian shaman who purportedly pierced six daggers through his chest, saying, “You can learn about God through your body.”

“I was up there,” he said, “with the creators of the universe.”

That saying became a kind of motto for Mr. Musafar, who spread his philosophy and practices through a magazine, Body Play and Modern Primitives Quarterly, and through a school in San Francisco, Fakir Body Piercing and Branding Intensives. Founded in 1991, the school had trained 1,400 people as of 2017, the San Francisco Chronicle reported last year.

Mr. Musafar also toured the country and appeared in television specials and documentaries, most notably the 1985 film “Dances Sacred and Profane,” directed by Dan and Mark Jury. The documentary featured Gatewood, whom Mr. Musafar coaxed onto a bed of nails, and a scene in which Mr. Musafar hung naked from a cottonwood tree, suspended by ropes attached to pins in his chest — the result of deep piercings that, he said, were performed “under trance” and left no bleeding or trace of injury.

He described the practice as a variation on a Native American Sun Dance ritual, which he encountered while growing up on an Indian reservation in South Dakota. (Mr. Musafar was not an American Indian, a fact that led some critics to accuse him of cultural appropriation.)

After hanging for two or three hours in a “ripping flesh ceremony,” he then hung “for 20 minutes on a rope attached to iron hooks that go through holes in his chest,” the Times reported. Mr. Musafar later compared the experience to watching the final, psychedelic scenes of “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

“I was up there,” he said, “with the creators of the universe.”

Mr. Musafar was born in Aberdeen, S.D., on Aug. 10, 1930. His father was a mechanic, and his mother was a homemaker who wanted him to become a Lutheran minister.

“I found you could get by better in this world if you didn’t flaunt your differences,” Mr. Musafar told Larratt, claiming that before entering puberty he had psychometric and psychokinetic abilities. He affected an interest in photography, he said, as a cover for his primary hobby, which he feared would get him committed to an insane asylum.

“I could go into my mother’s fruit cellar, lock the door, and I was always developing film under a red light,” he said. “Actually I would be in there ripping flesh.”

Mr. Musafar graduated in 1952 from Northern State Teachers College (now Northern State University) in Aberdeen. After Army service during the Korean War, he received a master’s degree in technical theater and creative writing from San Francisco State University in 1956. He taught ballroom dance before entering advertising.

In 1990, Mr. Musafar married Dubois, a former dominatrix who teaches bondage, discipline and sadomasochism play to couples. They had long known one another, she told the Chronicle, but her affection for him blossomed after the premiere of “Dances Sacred and Profane.” “I saw him hanging by flesh hooks,” she said, “and I fell in love with him in that moment.”

In addition to his wife of Menlo Park, survivors include a stepson; a brother; and a sister.

To those who said his practices were too extreme, Mr. Musafar responded that his body modifications were only a few steps removed from yoga, sun tanning or the wearing of high heels, each of which he considered a form of “body play.”

“There are many paths up the mountain,” he often said in interviews, quoting the spiritual teacher Ram Dass, “but the view at the top is the same.”

This article was originally published in the Washington Post and written by Harrison Smith.